WAYIPUNGA

Walking with young mob to shape our future

Wayipunga (‘supporting young people’ in Dja Dja Wurrung language) is your go-to youth participation resource for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people. This framework provides workers, organisations and government with strategies to support our young mob’s participation in decision-making processes.

Explore the Wayipunga resource

Wayipunga is made up of 3 sections:

About us

Wayipunga (supporting young people) is an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth participation framework that provides workers, organisations and government with strategies to support young people’s participation in decision-making processes. The framework is made up of three sections: Values, Knowledge and Actions. All three are interrelated and each informs the other.

At KYC, we acknowledge and respect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people as decision-makers and leaders in their own right. In recognition of this and through our work, we saw a great need to establish a resource and framework that would support both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and mainstream services to better engage and enable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people to participate fully in matters that affect their lives through a best practice model that was accessible across sectors.

Wayipunga calls on everyone who works with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people to join us in sharing their voices and practising the principles of meaningful engagement to ensure they are empowered to participate in matters that are important to them.

Wayipunga recognises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of doing business. Youth participation was a fundamental principle of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community operations and how we kept our children, young people and families strong for 80,000 years.

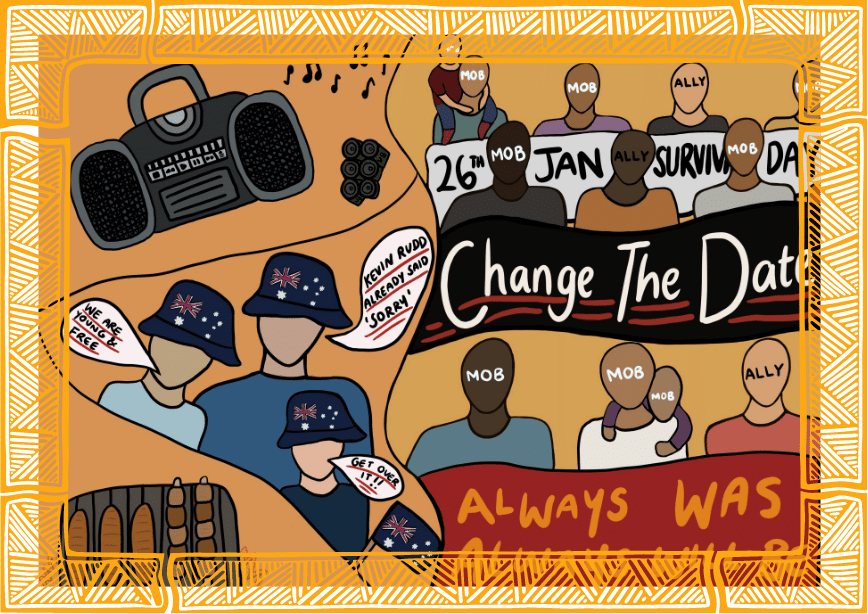

However, since colonisation, we have seen the results of poor systems, policies and legislations have a direct impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people. Many of these still have not been adequately responded to. This has negative impacts on the way in which our young people engage with services and programs, which reinforces the importance of working proactively to challenge the ‘normality’ of systems which exist today.

Wayipunga came about through KYC’s continuous engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, which highlighted both the good and bad practices of youth participation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and the need to highlight the good practices.

We recognised that young people had to be at the heart of the resource. We ran a series of consultations across the state to understand the needs, barriers and enablers of youth participation. These consultations sought to engage people working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, and the experts themselves: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.

In the process of developing these consultations, we knew that we had to identify what would be safe engagement and create positive feedback loops with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people so that systems are delivering to young people in the ways they need them to.

Wayipunga in Dja Dja Wurrung language means ‘supporting young people.’ We acknowledge Dja Dja Wurrung Aboriginal Clans Corporation for giving us permission to use their language for this project.

How to use the Wayipunga resource

Wayipunga is made up of three sections:

- Values

- Knowledge

- Actions

All three are interrelated and each informs the other. It is intended to be read in order — please start with 1. Values, move to 2. Knowledge, and finish with 3. Actions.

These sections have been developed with young people to provide context for the complex and diverse experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in Victoria. This should prompt you, the youth worker or stakeholder, to consider ‘what’ or ‘how’ you can respond to these realities.

The third section, ‘Actions’, outlines different styles of approaches you can adopt when identifying what sort of circumstances, barriers or concerns may be present when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.

KYC acknowledges that youth participation is an ongoing practice and subjective by nature. Therefore, this resource should be used in accordance with guiding everyday practices associated with engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people. It is by no means a form of cultural awareness training or a checklist.

Please see the glossary if you require further explanation of any terms used throughout this resource.

After you have explored the Wayipunga resource, we encourage you to consider additional training opportunities for you and/or your organisation with the KYC team. Please contact us for more information.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures are the oldest surviving cultures on Earth, dating back 80,000+ years. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures have thrived for millennia despite the impacts of 230+ years of colonisation, demonstrating the resilience of culture as central to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities.

Australia is built on the lands and waters of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have never ceded sovereignty of these lands.

Australian society has a great deal to gain from taking the time to learn, honour and respect the culture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities.

Meaningful youth participation practices embed and celebrate culture, family and community.

‘Indigenous peoples have the right of self-determination. By that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.’

Article 3: UN General Assembly’s Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Self-determination promotes agency and choice. It recognises the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the custodians of their traditional lands and waters and ensures Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have the resources and capacity to control the future of their own communities.

In this context, this could mean enabling the space, time and resources for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to establish what self-determination means for themselves and their communities. Sometimes it can be as simple as considering, accepting, and empowering different perspectives. This is particularly important given the social and historical contexts outlined in Wayipunga.

Overall, what space exists in your community or workplace for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to decide what they need? It’s important to determine — if at all and depending on the context — how non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, organisations and governments can support self-determination too.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation enriches Australian society. Involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people provides insight into society that can’t be gained from anywhere else.

Almost sixty per cent of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community in Victoria is under the age of 25. This means that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people make up more than half of the population of their communities.

Valuing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s voices as a meaningful contribution to Australian society can be achieved through youth participation.

- Article 12

- Article 13

- Article 15

Through participation, it is more likely that services and programs will be designed for the specific needs of individuals and communities. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people have real knowledge and insight into their experiences and those of their communities that should influence decision-making about the services, programs and systems that impact their lives.

Values

Values is the first section of Wayipunga. It provides the foundations for the ways in which workers, organisations and governments support and embrace Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, families and communities

Self-determination

Young people’s participation

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, families and communities

Respecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, families and communities as First Nations and sovereign custodians of land

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures are the oldest surviving cultures on Earth, dating back 80,000+ years. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures have thrived for millennia despite the impacts of 230+ years of colonisation, demonstrating the resilience of culture as central to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities.

Australia is built on the lands and waters of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have never ceded sovereignty of these lands.

Australian society has a great deal to gain from taking the time to learn, honour and respect the culture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities.

Meaningful youth participation practices embed and celebrate culture, family and community.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture has enormous strengths and the potential to provide children with a wonderfully rich childhood, family life and cultural and spiritual life. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families can be strong and powerful and provide valuable social capital for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (SNAICC, 2006, p. 7).

Self-determination

Supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as decision-makers and sovereign peoples

Self-determination promotes agency and choice. It recognises the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the custodians of their traditional lands and waters and ensures Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have the resources and capacity to control the future of their own communities.

In this context, this could mean enabling the space, time and resources for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to establish what self-determination means for themselves and their communities. Sometimes it can be as simple as considering, accepting, and empowering different perspectives. This is particularly important given the social and historical contexts outlined in Wayipunga.

Overall, what space exists in your community or workplace for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to decide what they need? It’s important to determine — if at all and depending on the context — how non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, organisations and governments can support self-determination too.

At an individual level, self-determination means that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people have control of decisions about matters that affect their lives. Meaningful youth participation practices support and work to advance young people’s self-determination. ‘Indigenous peoples have the right of self-determination. By that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.’ Article 3: UN General Assembly’s Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Young people’s participation

Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation as a meaningful contribution to Australian society

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation enriches Australian society. Involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people provides insight into society that can’t be gained from anywhere else.

Almost sixty per cent of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community in Victoria is under the age of 25. This means that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people make up more than half of the population of their communities.

Valuing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s voices as a meaningful contribution to Australian society can be achieved through youth participation.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture has enormous strengths and the potential to provide children with a wonderfully rich childhood, family life and cultural and spiritual life. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families can be strong and powerful and provide valuable social capital for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (SNAICC, 2006, p. 7).

Youth participation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people occurs when young people have genuine and meaningful involvement in decision-making processes in a way that recognises and values their rights to self-determination, experiences, knowledge and skills.

Through participation, it is more likely that services and programs will be designed for the specific needs of individuals and communities. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people have real knowledge and insight into their experiences and those of their communities that should influence decision-making about the services, programs and systems that impact their lives.

You have the right to say what you think should happen when adults are making decisions that affect you, and to have your opinions considered.

– Article 12

You have the right to get, and to share, information if the information is not damaging to yourself or others.

– Article 13

You have the right to meet with other children and young people and to join groups and organisations, if this does not stop other people from enjoying their rights.

– Article 15

This section outlines the knowledge required for workers to understand Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s experiences. As a worker, you should build this knowledge into your practice with young people.

In this section

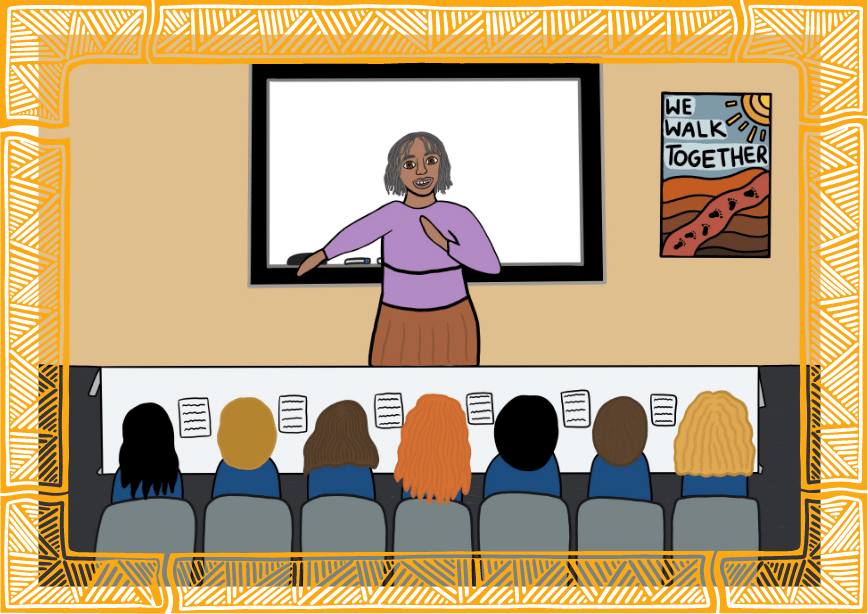

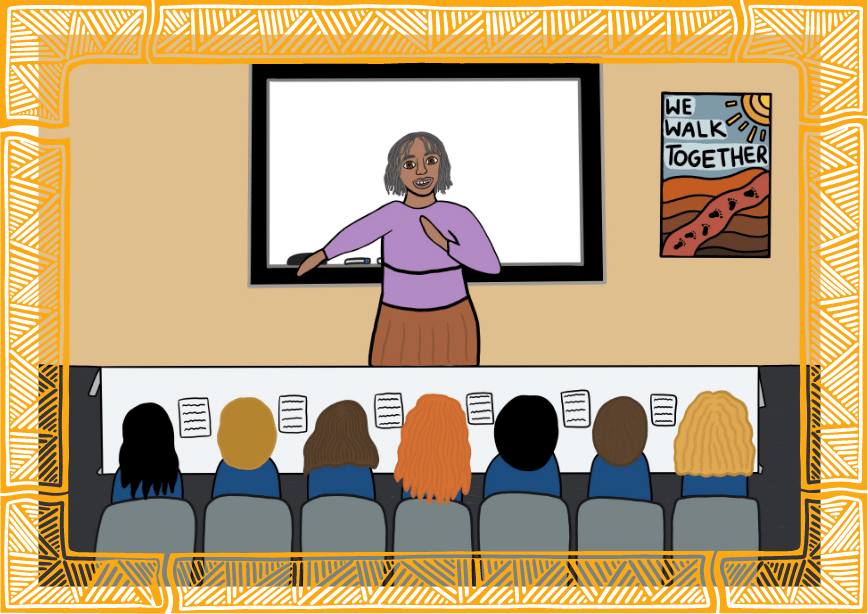

Workers and organisations have a responsibility when engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people to ensure that their engagement is culturally aware and culturally safe.

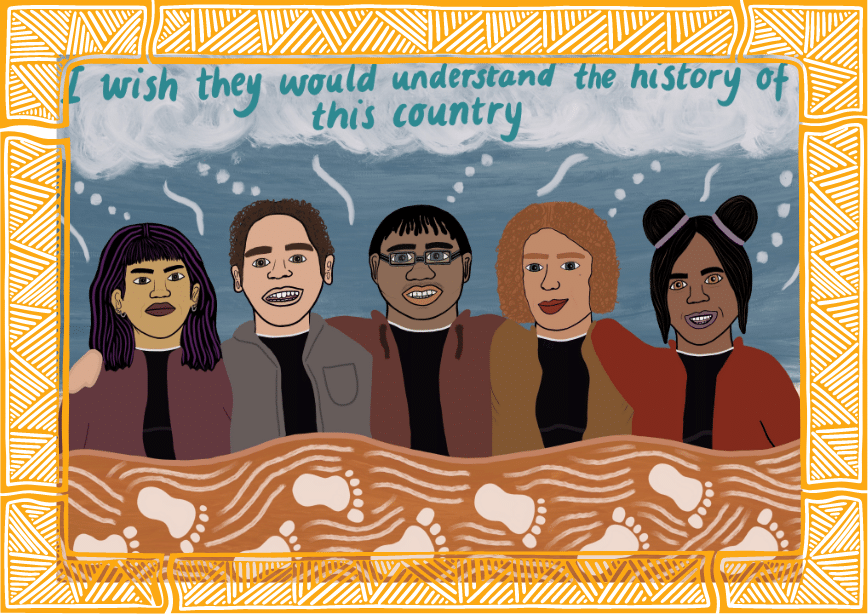

Providing opportunities that are genuine and meaningful for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people starts with having a clear understanding of Australia’s colonial history.

The ongoing trauma, grief and loss of culture that resulted from colonisation still has a significant impact on the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, their families and communities today.

A lack of knowledge regarding the colonisation of Australia and the ongoing impacts of European invasion on the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can provide significant barriers to young people’s genuine and meaningful participation.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and communities deliver localised cultural awareness training. KYC strongly recommends that organisations and workers undertake localised and place-based cultural safety training delivered by Traditional Owner organisations and/or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Organisations.

For reference, you’ll find cultural awareness and cultural safety training options at Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation Inc. (VACCHO).

There are also many other resources available to assist you building your knowledge. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but can be used as a starting point:

• The Victorian Government’s Deadly Questions website

• Share Our Pride Reconciliation website

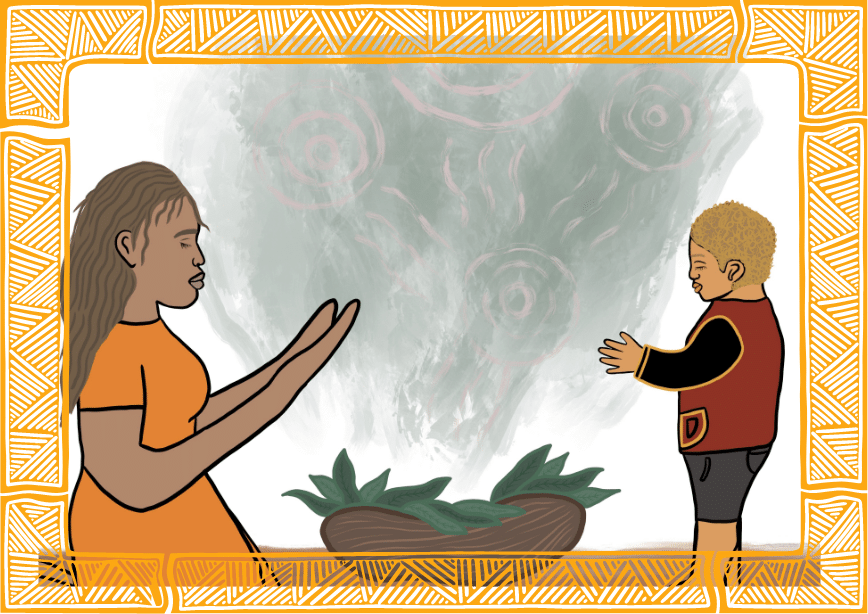

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country are interrelated and interdependent.

Strong connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country promotes a sense of belonging, positive wellbeing and resilience. This supports Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people know who they are according to how they relate to culture, family, kinship, community and Country. This understanding of interrelated and interdependent connections differs from Western ideas of young people that focus heavily on the individual. Thinking about young people individually has been and often still is “privileged over Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural ways of knowing and understanding.” (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

“For too long Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children have been assessed using measures and assessment approaches which do not take into account their culture, beliefs, connection to community and place, spirituality and their individual experiences. Furthermore, the assessment of an individual’s social and emotional status independent of the family and community is an alien concept to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as well as being ecologically uninformed.” (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

Workers and organisations have a responsibility when engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people to support young people’s connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country.

This includes embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s connections when developing opportunities that seek Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing are holistic and part of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sense of identity and meaning…. These were deep encompassing systems of knowledge and knowing, and embedded in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s very being.” (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

Past and ongoing impacts of colonisation have and may still be influencing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country.

When colonial understandings are preferred over Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways, this can have significant implications for how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people are able to, choose to, or refrain from, participating.

When building knowledge about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country, workers and organisations should build this knowledge through a localised and place-based lens. This recognises and respects the significance of place as strong connections for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities.

In a perfect world, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people would have these strong connections. However, as we know from the effects of colonisation and family dynamics, what ‘strong connections’ look like will differ for families. That is why this section exists to reinforce the importance of firstly identifying what ‘strong connections’ look like for any given young person, and secondly, supporting the ‘strongest connections’ for them.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, like all young people, are influenced by the social context in which they live.

Considering a young person within their social context involves reflecting on the social and structural forces that impact on a young person’s life, in order to be responsive to a young person’s needs, experiences and the barriers limiting a young person’s life opportunities (Code of Ethical Practice — A First Step for the Victorian Youth Sector 2007, p.5).

Young people do not exist in isolation, instead young people are influenced, shaped and sometimes limited by their social context (Code of Ethical Practice — A First Step for the Victorian Youth Sector 2007, p. 15).

The idea of considering a young person within their social context, as opposed to individually, mirrors the holistic and interdependent nature of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems.

The topics discussed below are intended to provide a starting point to assist workers and organisations in building knowledge around the social context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in contemporary society. They are by no means intended to be a comprehensive representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s experiences, rather a snapshot gathered in relation to youth participation.

Considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s social context when seeking participation will assist in getting the best outcome for young people, as well as workers and organisations.

Koorreen Enterprises runs workshops on cultural loads, healing lateral violence, and cultural awareness, among other topics.

Using the knowledge from this resource and embedding it into your practice will support workers and organisations in addressing structural barriers.

A fantastic resource that can support your knowledge building in this area is Decolonising Solidarity by Clare Land.

Decolonisation is a process that involves a conscious effort to recognise where dominant colonial systems are at play, and to replace these with space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s knowledge, experiences and voices.

Importantly, decolonisation moves from a deficit vision of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to one that focuses on strengths, capabilities and resilience.

We live on the traditional lands and waters of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. Contemporary Australian society is based on colonial systems that rarely incorporate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, practices or knowledge systems and actively marginalise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Colonialism is not confined to history. It continues wherever we have dominant, mainstream systems that fail to recognise the strength and value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s knowledge, experiences and voices.

When the colonial systems and structures that govern society fail to recognise the value and strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s knowledge, experiences and voices, these systems and structures perpetuate barriers to the genuine and meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people face many barriers to participation within colonial systems and structures.

Decolonisation requires self-reflection on the part of workers and organisations. We need to ensure programs and services are developed by or with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and their communities, instead of for them.

In doing this, workers learn to walk with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and their communities.

This work requires ongoing reflection on the part of workers and organisations and strong collaboration or partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations.

While youth participation has been widely conceptualised and discussed in other contexts, it is not often acknowledged or considered in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s experiences and social context.

Youth participation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people occurs when young people have genuine and meaningful involvement in decision-making processes in a way that recognises and values their rights to self-determination, experiences, knowledge and skills.

Providing genuine and meaningful participation and engagement opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people requires workers and organisations to build an understanding of youth participation and the value of involving young people as an integral part of communities and wider society, as well as within areas such as program development, policy reform and service delivery.

Throughout the project, KYC spoke with many workers from around Victoria working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people about a range of topics to do with youth participation: how workers were practicing youth participation in their work; what was working well in regards to youth participation in their area; and what they saw as challenges to participation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.

Workers and organisations will need to consider how the opportunity is genuinely creating space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s voices and whether the opportunity will be meaningful for the young people involved.

As workers and organisations, when we consider our ethical obligations to young people through a lens of decolonisation, we create space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s voices and participation in systems and structures that previously silenced or ignored them.

The Code of Ethical Practice for the Victorian Youth Sector (The Code) provides a set of principles and practice responsibilities to assist workers and organisations in working with young people and supporting young people’s genuine and meaningful participation.

If you or your organisation are not familiar with The Code or need a refresher, Youth Affairs Council of Victoria (YACVic) runs Code of Ethical Practice training that can equip workers and organisations with skills in ethical practice when engaging with young people.

Overwhelmingly, workers spoke of a significant lack of programs, services or groups available for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people within communities around Victoria.

Gaps in knowledge for culturally safe engagement

Many workers expressed a desire to learn more about engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in culturally safe ways. This emphasised that there are many gaps in knowledge around culturally safe engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.

Building strong relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

A vital element of culturally safe engagement is workers and organisations building relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, as well as their families and communities, where it is appropriate to do so.

Allowing adequate time for the development of rapport and trust when building relationships respects Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and ways of working and values strong connections when engaging with young people and seeking their participation.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people navigate multiple worlds, often referred to by young people as ‘living in two worlds’– the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander world, and the non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander world.

It is important to recognise the intersection of worlds that some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people navigate in addition to these Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander worlds. For example, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people that identify as LGBTQIA+; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people with a disability; or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people within the justice or out-of-home care systems.

Meaningful youth participation opportunities consider intersecting worlds, ensuring opportunities for participation are diverse and inclusive.

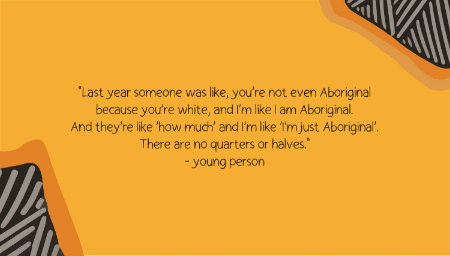

Justifying Aboriginality

For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, navigating non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander worlds involves questions about their identity and having to justify their Aboriginality.

Needing to justify their identity poses challenges and barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s genuine and meaningful participation.

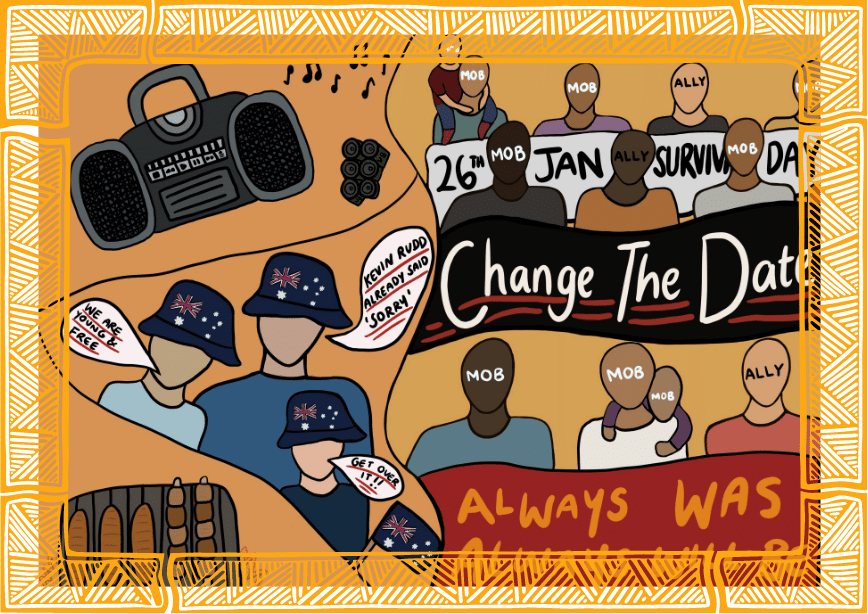

Racism and discrimination

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people spoke about the widespread nature of discrimination and racism in Australian society.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people face experiences of overt racism and covert racism, as well as discrimination within workplaces, institutions and Australian society. These experiences of racism and discrimination affect young people’s want or ability to participate.

Cultural loads are the invisible loads that people of other cultures or other social demographics carry.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it’s discrimination, it’s loss of language and culture. It’s also the fact that we have the highest suicide rate in the world, that we have an incredibly high incarceration rate, and that we’re continually required to justify our losses. It’s about all the pressures from not having free and easy access to your culture (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

Cultural loads are present in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in many forms. The topics discussed in this section so far—navigating multiple worlds, justifying identity, racism and discrimination —all contribute to the cultural loads that young people carry.

Throughout this project, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people spoke to what it means to them to carry cultural loads.

Understanding and respecting cultural loads and being responsive to them can support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s ability and willingness to participate.

Young people’s roles within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

Where the topic of Elders and community leaders came up with young people in our consultations, there was great respect for Elders and leaders in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, and respect for the traditional roles and protocols that these Elders and leaders have within communities.

Some young people identified the changing role of young people within contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and society. Young people discussed the complexities that they can face in participating meaningfully within their communities while still being respectful of and not undermining the longstanding cultural pillar of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies.

Navigating community conflict and lateral violence

“Lateral violence occurs worldwide in all minorities and particularly Indigenous peoples where its roots lie in colonisation, oppression, intergenerational trauma and ongoing experiences of racism and discrimination.” (Bamblett et. al. 2011)

Lateral violence grows when a community feels oppressed, displaced, unsafe and without safe frameworks for direction (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

Young people discussed the presence of community conflict and lateral violence and the affects it can have on them and their families.

For some young people, perception from members of the community provided a big barrier to their experiences of participation within the community.

When discussing conflict within their communities, conflict was also referred to as ‘community politics’ and was often discussed when young people spoke about challenges within processes that involved community decision-making.

The challenges that conflict within communities poses to young people’s ability to be included within community and within decision-making processes were highlighted in our consultations.

Young people spoke about the desire for unity within their communities and how this would help them to feel more comfortable to participate.

Each young person has different experiences and as such, it is important to consider a young person’s individual needs, experiences and barriers.

Considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s social context when seeking participation will assist in getting the best outcome for young people, as well as workers and organisations.

Koorreen Enterprises runs workshops on cultural loads, healing lateral violence, and cultural awareness, among other topics.

Knowledge

Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people may involve a new set of skills and knowledge, particularly for non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers and organisations, or for those that require support in engaging with young people.

This section outlines the knowledge required for workers to understand Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s experiences. As a worker, you should build this knowledge into your practice with young people.

In this section

Historical context

Strong connections

Social context

Decolonisation

Genuine and meaningful engagement

Historical context

Knowing the past

Workers and organisations have a responsibility when engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people to ensure that their engagement is culturally aware and culturally safe.

Providing opportunities that are genuine and meaningful for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people starts with having a clear understanding of Australia’s colonial history.

The ongoing trauma, grief and loss of culture that resulted from colonisation still has a significant impact on the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, their families and communities today.

A lack of knowledge regarding the colonisation of Australia and the ongoing impacts of European invasion on the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can provide significant barriers to young people’s genuine and meaningful participation.

The expectation to be the ‘expert’ on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history, culture and identity is a significant barrier to many young people’s want or ability to participate.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and communities deliver localised cultural awareness training. KYC strongly recommends that organisations and workers undertake localised and place-based cultural safety training delivered by Traditional Owner organisations and/or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Organisations.

For reference, you’ll find cultural awareness and cultural safety training options at <strong>Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation Inc. (VACCHO)</strong>.

There are also many other resources available to assist you building your knowledge. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but can be used as a starting point:

• The Victorian Government’s Deadly Questions website

• Share Our Pride Reconciliation website

Strong connections

Understanding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country are interrelated and interdependent.

Strong connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country promotes a sense of belonging, positive wellbeing and resilience. This supports Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people know who they are according to how they relate to culture, family, kinship, community and Country. This understanding of interrelated and interdependent connections differs from Western ideas of young people that focus heavily on the individual. Thinking about young people individually has been and often still is “privileged over Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural ways of knowing and understanding.” (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

“For too long Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children have been assessed using measures and assessment approaches which do not take into account their culture, beliefs, connection to community and place, spirituality and their individual experiences. Furthermore, the assessment of an individual’s social and emotional status independent of the family and community is an alien concept to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as well as being ecologically uninformed.” (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

The Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Wheel works in two ways. The first is that the inner circle represents everything that a young person needs to feel holistically well. When each of these things are part of a young person’s life, they are more likely to feel fulfilled as an Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander young person. The second is the outer circle. Each of these components represent things that a young person can’t control yet affect their wellbeing i.e. social determinants such as 26 January.

Figure 1. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Emotional Wellbeing Framework (Gee et. al. 2013)

This wheel can act as a practical guide for supporting strong connections. How can you support a young person to fulfil each of the sections in the inner circle? How can you support a young person to navigate the factors on the outer?

Workers and organisations have a responsibility when engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people to support young people’s connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country.

This includes embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s connections when developing opportunities that seek Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing are holistic and part of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sense of identity and meaning…. These were deep encompassing systems of knowledge and knowing, and embedded in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s very being.” (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

Past and ongoing impacts of colonisation have and may still be influencing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country.

When colonial understandings are preferred over Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways, this can have significant implications for how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people are able to, choose to, or refrain from, participating.

When building knowledge about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s connections to culture, family, kinship, community and Country, workers and organisations should build this knowledge through a localised and place-based lens. This recognises and respects the significance of place as strong connections for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities.

In a perfect world, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people would have these strong connections. However, as we know from the effects of colonisation and family dynamics, what ‘strong connections’ look like will differ for families. That is why this section exists to reinforce the importance of firstly identifying what ‘strong connections’ look like for any given young person, and secondly, supporting the ‘strongest connections’ for them.

Social context

The worlds that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people live in

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, like all young people, are influenced by the social context in which they live.

Considering a young person within their social context involves reflecting on the social and structural forces that impact on a young person’s life, in order to be responsive to a young person’s needs, experiences and the barriers limiting a young person’s life opportunities (Code of Ethical Practice — A First Step for the Victorian Youth Sector 2007, p.5).

Young people do not exist in isolation, instead young people are influenced, shaped and sometimes limited by their social context (Code of Ethical Practice — A First Step for the Victorian Youth Sector 2007, p. 15).

The idea of considering a young person within their social context, as opposed to individually, mirrors the holistic and interdependent nature of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems.

The topics discussed below are intended to provide a starting point to assist workers and organisations in building knowledge around the social context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in contemporary society. They are by no means intended to be a comprehensive representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s experiences, rather a snapshot gathered in relation to youth participation.

Each young person has different experiences and as such, it is important to consider a young person’s individual needs, experiences and barriers.

Considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s social context when seeking participation will assist in getting the best outcome for young people, as well as workers and organisations.

Koorreen Enterprises runs workshops on cultural loads, healing lateral violence, and cultural awareness, among other topics.

Decolonisation

Challenging accepted norms and embedding strengths-based ways of working

Decolonisation is a process that involves a conscious effort to recognise where dominant colonial systems are at play, and to replace these with space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s knowledge, experiences and voices.

Importantly, decolonisation moves from a deficit vision of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to one that focuses on strengths, capabilities and resilience.

We live on the traditional lands and waters of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. Contemporary Australian society is based on colonial systems that rarely incorporate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, practices or knowledge systems and actively marginalise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Colonialism is not confined to history. It continues wherever we have dominant, mainstream systems that fail to recognise the strength and value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s knowledge, experiences and voices.

When the colonial systems and structures that govern society fail to recognise the value and strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s knowledge, experiences and voices, these systems and structures perpetuate barriers to the genuine and meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people face many barriers to participation within colonial systems and structures.

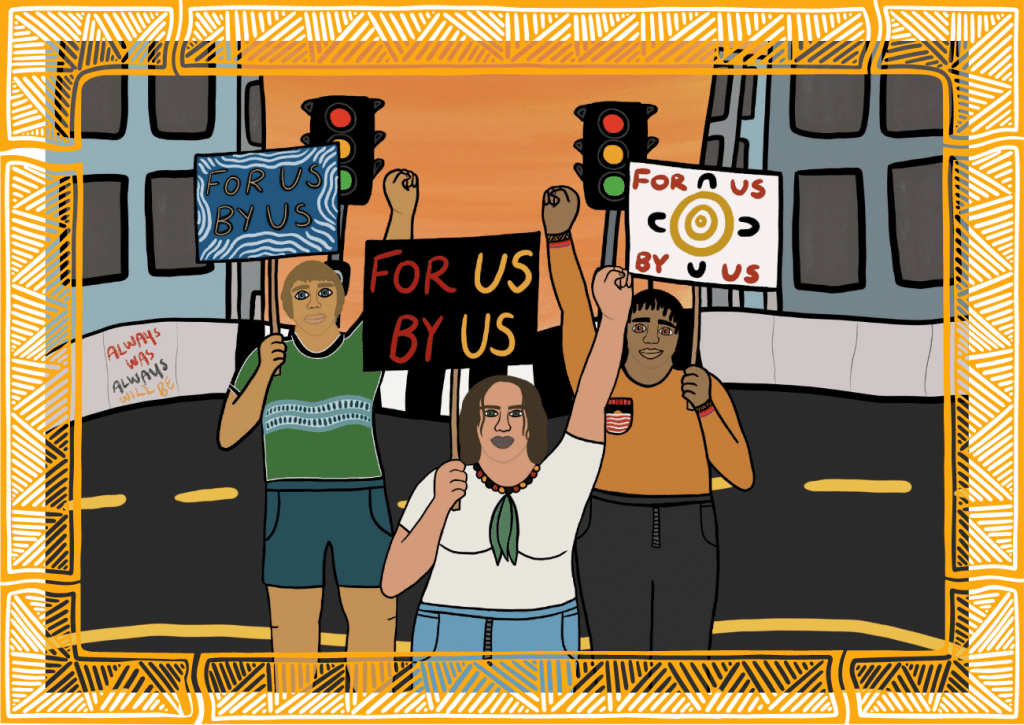

Decolonisation requires self-reflection on the part of workers and organisations. We need to ensure programs and services are developed by or with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and their communities, instead of for them.

In doing this, workers learn to walk with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and their communities.

This work requires ongoing reflection on the part of workers and organisations and strong collaboration or partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations.

Providing genuine and meaningful youth participation opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people requires the decolonisation of systems and structures; of organisations, policies and engagement strategies and of a workers individual practice.

Using the knowledge from this resource and embedding it into your practice will support workers and organisations in addressing structural barriers.

A fantastic resource that can support your knowledge building in this area is Decolonising Solidarity by Clare Land.

Genuine and meaningful engagement

Genuine and meaningful participation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people

While youth participation has been widely conceptualised and discussed in other contexts, it is not often acknowledged or considered in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s experiences and social context.

Youth participation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people occurs when young people have genuine and meaningful involvement in decision-making processes in a way that recognises and values their rights to self-determination, experiences, knowledge and skills.

Providing genuine and meaningful participation and engagement opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people requires workers and organisations to build an understanding of youth participation and the value of involving young people as an integral part of communities and wider society, as well as within areas such as program development, policy reform and service delivery.

Throughout the project, KYC spoke with many workers from around Victoria working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people about a range of topics to do with youth participation: how workers were practicing youth participation in their work; what was working well in regards to youth participation in their area; and what they saw as challenges to participation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.

There may be several ethical considerations in providing participation opportunities to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, particularly if the systems and structures within which these opportunities are posed haven’t previously considered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of working.

Workers and organisations will need to consider how the opportunity is genuinely creating space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s voices and whether the opportunity will be meaningful for the young people involved.

As workers and organisations, when we consider our ethical obligations to young people through a lens of decolonisation, we create space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s voices and participation in systems and structures that previously silenced or ignored them.

The Code of Ethical Practice for the Victorian Youth Sector (The Code) provides a set of principles and practice responsibilities to assist workers and organisations in working with young people and supporting young people’s genuine and meaningful participation.

If you or your organisation are not familiar with The Code or need a refresher, Youth Affairs Council of Victoria (YACVic) runs Code of Ethical Practice training that can equip workers and organisations with skills in ethical practice when engaging with young people.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people navigate multiple worlds, often referred to by young people as ‘living in two worlds’– the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander world, and the non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander world.

It is important to recognise the intersection of worlds that some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people navigate in addition to these Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander worlds. For example, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people that identify as LGBTQIA+; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people with a disability; or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people within the justice or out-of-home care systems.

Meaningful youth participation opportunities consider intersecting worlds, ensuring opportunities for participation are diverse and inclusive.

For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, navigating non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander worlds involves questions about their identity and having to justify their Aboriginality.

Needing to justify their identity poses challenges and barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s genuine and meaningful participation.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people spoke about the widespread nature of discrimination and racism in Australian society.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people face experiences of overt racism and covert racism, as well as discrimination within workplaces, institutions and Australian society. These experiences of racism and discrimination affect young people’s want or ability to participate.

Cultural loads are the invisible loads that people of other cultures or other social demographics carry.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it’s discrimination, it’s loss of language and culture. It’s also the fact that we have the highest suicide rate in the world, that we have an incredibly high incarceration rate, and that we’re continually required to justify our losses. It’s about all the pressures from not having free and easy access to your culture (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

Cultural loads are present in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in many forms. The topics discussed in this section so far—navigating multiple worlds, justifying identity, racism and discrimination —all contribute to the cultural loads that young people carry.

Throughout this project, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people spoke to what it means to them to carry cultural loads.

Understanding and respecting cultural loads and being responsive to them can support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s ability and willingness to participate.

Where the topic of Elders and community leaders came up with young people in our consultations, there was great respect for Elders and leaders in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, and respect for the traditional roles and protocols that these Elders and leaders have within communities.

Some young people identified the changing role of young people within contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and society. Young people discussed the complexities that they can face in participating meaningfully within their communities while still being respectful of and not undermining the longstanding cultural pillar of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies.

“Lateral violence occurs worldwide in all minorities and particularly Indigenous peoples where its roots lie in colonisation, oppression, intergenerational trauma and ongoing experiences of racism and discrimination.” (Bamblett et. al. 2011)

Lateral violence grows when a community feels oppressed, displaced, unsafe and without safe frameworks for direction (Bamblett et. al. 2011).

Young people discussed the presence of community conflict and lateral violence and the affects it can have on them and their families.

For some young people, perception from members of the community provided a big barrier to their experiences of participation within the community. When discussing conflict within their communities, conflict was also referred to as ‘community politics’ and was often discussed when young people spoke about challenges within processes that involved community decision-making. The challenges that conflict within communities poses to young people’s ability to be included within community and within decision-making processes were highlighted in our consultations. Young people spoke about the desire for unity within their communities and how this would help them to feel more comfortable to participate.Each young person has different experiences and as such, it is important to consider a young person’s individual needs, experiences and barriers.

Considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s social context when seeking participation will assist in getting the best outcome for young people, as well as workers and organisations.

Koorreen Enterprises runs workshops on cultural loads, healing lateral violence, and cultural awareness, among other topics.

In this section

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation celebrate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture. Here’s some ways this can be done:

· Identify and acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land that your work takes place upon. Acknowledging Country can be an act of respect and solidarity and does not necessarily need to be done by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

· Consider creating a policy that embeds this practice into your organisation’s culture.

· Involve Elders and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members and culture in community events.

· Fly the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags.

· Display geographic posters and maps which outline Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language groups and nations.

· Promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander faces in your organisation and showcase Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art in your workplace.

· Recognise significant dates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and take the time to reflect on the importance of these

Building partnerships that are based in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge fosters cultural safety, promotes trust, respect and strong relationships.

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and build partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities by:

- Building relationships and partnerships with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations in your region.

When doing so, consider what the opportunity might be for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations in establishing connections with your program, service or organisation to avoid adding unnecessary loads on to communities and organisations. It’s important to reflect on the fact that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples make up roughly 3% of the population in Australia and their knowledge and input is often in high demand for collaboration and partnerships. This is certainly not to suggest that you should work without involving them, rather that consideration should be given to what you may be asking of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations and what you may be able to do yourself.

- Involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members in the planning and implementation of participation opportunities.

Can these be led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities?

· Involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s family, extended kin and Elders in your work, were appropriate.

· Utilising existing networks and resources to help you expand your networks.

· Considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge in your day-to-day activities – are you framing your work in holistic, interdependent frameworks that consider Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s strong connections? Are you considering localised and place-based nuances and ways of working in your day-to-day activities?

Cultural safety is not achievable through training alone. On an individual level, building ongoing relationships and partnerships, as well as continually reflecting on practice is key to building cultural safety.

Organisations and institutions also need to embed processes and structures that implement and foster cultural safety.

· Understanding the contemporary social context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, including cultural loads, sorry business and lateral violence and how these may influence a young person’s ability or want to participate. Provide support and help young people to unpack this stuff, recognising ethical boundaries around ‘taking sides’ or ‘trying to fix’ young people’s lived experience.

· Avoiding generalisations and stereotypes about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and challenging them when you hear them.

· Acknowledging the resultant trauma of colonisation in Australia and reaffirming young people’s pride in cultural identity, connection to Country and participation in community to support healing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

· Avoiding tokenism when seeking participation from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people. There are many ways to avoid tokenism, but a good place to start is reflecting on whether you are seeking Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation on a varied range of topics and not only on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs.

· Acknowledging where culturally unsafe practice occurs and be accountable to the young people and communities involved.

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation challenge barriers by:

What barriers are you putting in place in your individual practice?

• Considering barriers at all levels.

Are there logistical barriers to young people’s participation, such as money, transport or time that your program, service or organisation may be able to mitigate? Are there potential barriers in the way you’re attempting to communicate with young people?

• Considering your language, verbal and non-verbal communication and approach. Are there barriers within the way your organisation operates or appeals to young people?

• Considering if Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people would feel represented or acknowledged within your organisation, or whether there may be structures restricting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s desire or ability to get involved. How can you reduce these barriers?

• Considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge in your day-to-day activities – are you framing your work in holistic, interdependent frameworks that consider Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s strong connections? Are you considering localised and place-based nuances and ways of working in your day-to-day activities?

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation increase accessibility by:

• Avoiding ‘othering’ – building knowledge and familiarity with diversity and difference can support this. Cultural awareness training is a good place to start.

• Thinking outside your usual modes of engagement – ask young people how they’d like to be involved.

• Providing a broad range of opportunities for young people to be involved in, avoiding opportunities being related to young people or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs, only.

• Mitigating logistical and practical barriers to young people’s participation.

• Providing ‘space’ for young people to gather, learn and share knowledge and ideas – this could be a physical space, online space, ongoing or one-off and should be dependent on the context and needs of young people.

• Considering whether a young person can do a task you might usually do yourself or outsource, or whether a young person may be able to do the task with you.

• Remunerating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people for their time and expertise.

• Reimbursing young people for any out-of-pocket expenses incurred in order to participate.

• Having a dedicated role or staff member committed to supporting the process of participation for young people and the navigation of adult-led spaces.

• Recognising the significance of historical and social context and the importance of strong connections, do you need to consider a different approach or way of working in order to enhance participation or engagement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people?

• Connecting young people to services and networks that can support their needs and aspirations.

• Considering intersections – how are LGBTIQA+ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people with a disability, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in the justice or out-of-home care systems able to participate?

• Providing training or mentoring that supports young people’s involvement in decision-making processes.

• Facilitating training and other skills-building opportunities for young people.

• Creating a youth participation framework for your program, service or organisation to support staff and stakeholders in committing to genuine and meaningful participation for young people.

• Working towards a systems-based shift that recognises young people as experts in their own experiences and values this experience as a level of expertise, working with young people as partners rather than recipients.

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation commit to continual learning by:

• Holding a planning session to reflect on how your program, service or organisation currently works with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and looking for areas of improvement – can youth participation become a standing item on your regular meeting agenda?

• Evaluating your program, service or organisation’s level of cultural awareness and cultural safety and looking for ways to improve or further embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge and ways of working. Make this ongoing.

• Reflecting on the language that you and your workplace uses - is it inclusive and strengths-based?

• Considering the current social and political climate and the effect this may have on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and the influence it may have on their participation or engagement – how might you or your organisation support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and show solidarity or allyship?

• Taking individual responsibility for cultural and historical education. Asking Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people to support your learning adds to the cultural loads that young people are already carrying.

• Self-care. There may be a level of discomfort that comes along with the process of unpacking important topics like colonisation and whiteness. While this work is vital to creating space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, workers and organisations should implement strategies and tools that support their wellbeing and learning journey.

Actions

This section is designed to help workers, organisations and communities embed the values and knowledge of the framework into everyday practice. None of the strategies provided below represent an exhaustive list and must be reflected on and implemented within a place-based and localised context.

In this section

Celebrate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture

Embed knowledge systems and build partnerships

Cultural safety

Challenge barriers

Increase accessibility

Continual learning

Celebrate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture

There are many ways in which workers, organisations and government can further recognise, represent, respect and celebrate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture.

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation celebrate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture. Here’s some ways this can be done:

– Organise for Traditional Owners to welcome you to Country at meetings and events, where appropriate.

– Identify and acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land that your work takes place upon. Acknowledging Country can be an act of respect and solidarity and does not necessarily need to be done by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

– Consider creating a policy that embeds this practice into your organisation’s culture.

– Involve Elders and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members and culture in community events.

– Fly the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags.

– Display geographic posters and maps which outline Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language groups and nations.

– Promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander faces in your organisation and showcase Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art in your workplace.

– Recognise significant dates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and take the time to reflect on the importance of these

Embed knowledge systems and build partnerships

Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and building partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, communities and organisations is vital to the genuine and meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.

Building partnerships that are based in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge fosters cultural safety, promotes trust, respect and strong relationships.

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and build partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities by:

– Building relationships and partnerships with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations in your region.

When doing so, consider what the opportunity might be for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations in establishing connections with your program, service or organisation to avoid adding unnecessary loads on to communities and organisations. It’s important to reflect on the fact that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples make up roughly 3% of the population in Australia and their knowledge and input is often in high demand for collaboration and partnerships. This is certainly not to suggest that you should work without involving them, rather that consideration should be given to what you may be asking of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations and what you may be able to do yourself.

– Involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members in the planning and implementation of participation opportunities.

Can these be led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities?

– Developing programs, services and opportunities underpinned by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of working and including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in the development as much as possible.

– Involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s family, extended kin and Elders in your work, were appropriate.

– Utilising existing networks and resources to help you expand your networks.

– Considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge in your day-to-day activities – are you framing your work in holistic, interdependent frameworks that consider Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s strong connections? Are you considering localised and place-based nuances and ways of working in your day-to-day activities?

Cultural safety

Cultural safety is “an environment that is safe for people: where there is no assault, challenge or denial of their identity, of who they are and what they need. It is about shared respect, shared meaning, shared knowledge and experience, of learning, living and working together with dignity and truly listening.” (Williams 1999, Cultural safety – What does it mean for our work practice? pp. 212f).

Cultural safety is not achievable through training alone. On an individual level, building ongoing relationships and partnerships, as well as continually reflecting on practice is key to building cultural safety.

Organisations and institutions also need to embed processes and structures that implement and foster cultural safety.

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation embed cultural safety by:

– Developing a Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) and embedding a continuous evaluation process for this plan within organisations and government departments.

– Understanding the contemporary social context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, including cultural loads, sorry business and lateral violence and how these may influence a young person’s ability or want to participate. Provide support and help young people to unpack this stuff, recognising ethical boundaries around ‘taking sides’ or ‘trying to fix’ young people’s lived experience.

– Avoiding generalisations and stereotypes about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and challenging them when you hear them.

– Acknowledging the resultant trauma of colonisation in Australia and reaffirming young people’s pride in cultural identity, connection to Country and participation in community to support healing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

– Avoiding tokenism when seeking participation from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people. There are many ways to avoid tokenism, but a good place to start is reflecting on whether you are seeking Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s participation on a varied range of topics and not only on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs.

– Acknowledging where culturally unsafe practice occurs and be accountable to the young people and communities involved.

Challenge barriers

There are many ways in which workers, organisations and government can challenge barriers that restrict Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s genuine and meaningful participation.

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation challenge barriers by:

• Challenging assumptions.

What barriers are you putting in place in your individual practice?

• Considering barriers at all levels.

Are there logistical barriers to young people’s participation, such as money, transport or time that your program, service or organisation may be able to mitigate? Are there potential barriers in the way you’re attempting to communicate with young people?

• Considering your language, verbal and non-verbal communication and approach. Are there barriers within the way your organisation operates or appeals to young people?

• Considering if Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people would feel represented or acknowledged within your organisation, or whether there may be structures restricting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s desire or ability to get involved. How can you reduce these barriers?

• Considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge in your day-to-day activities – are you framing your work in holistic, interdependent frameworks that consider Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s strong connections? Are you considering localised and place-based nuances and ways of working in your day-to-day activities?

Reflect on how your program, service or organisation can challenge systemic barriers that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people face.

Increase accessibility

There are many ways in which workers, organisations and government can make genuine and meaningful participation more accessible for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation increase accessibility by:

• Reflecting on why you want to increase the participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people – seeking participation for participation’s sake or for the profile of your organisation can be problematic.

• Avoiding ‘othering’ – building knowledge and familiarity with diversity and difference can support this. Cultural awareness training is a good place to start.

• Thinking outside your usual modes of engagement – ask young people how they’d like to be involved.

• Providing a broad range of opportunities for young people to be involved in, avoiding opportunities being related to young people or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs, only.

• Mitigating logistical and practical barriers to young people’s participation.

• Providing ‘space’ for young people to gather, learn and share knowledge and ideas – this could be a physical space, online space, ongoing or one-off and should be dependent on the context and needs of young people.

• Considering whether a young person can do a task you might usually do yourself or outsource, or whether a young person may be able to do the task with you.

• Remunerating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people for their time and expertise.

• Reimbursing young people for any out-of-pocket expenses incurred in order to participate.

• Having a dedicated role or staff member committed to supporting the process of participation for young people and the navigation of adult-led spaces.

• Breaking down silos – how can your work take more of a holistic, inclusive, interdependent approach?

• Recognising the significance of historical and social context and the importance of strong connections, do you need to consider a different approach or way of working in order to enhance participation or engagement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people?

• Connecting young people to services and networks that can support their needs and aspirations.

• Considering intersections – how are LGBTIQA+ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people with a disability, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in the justice or out-of-home care systems able to participate?

• Providing training or mentoring that supports young people’s involvement in decision-making processes.

• Facilitating training and other skills-building opportunities for young people.

• Creating a youth participation framework for your program, service or organisation to support staff and stakeholders in committing to genuine and meaningful participation for young people.

• Working towards a systems-based shift that recognises young people as experts in their own experiences and values this experience as a level of expertise, working with young people as partners rather than recipients.

Continual learning

Continual learning includes reflective practice and evaluation. Reflective practice involves reflecting on your own experiences in order to engage in a process of continuous learning with the aim of improving the way you work. Evaluation involves finding out if you’ve been successful and identifying areas for improvement.

Meaningful participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people can be enhanced when you or your organisation commit to continual learning by:

• Reflecting on and embedding the values, knowledge and actions outlined in this resource in order to support your practice and continuous learning journey.

• Holding a planning session to reflect on how your program, service or organisation currently works with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and looking for areas of improvement – can youth participation become a standing item on your regular meeting agenda?

• Evaluating your program, service or organisation’s level of cultural awareness and cultural safety and looking for ways to improve or further embed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge and ways of working. Make this ongoing.

• Reflecting on the language that you and your workplace uses – is it inclusive and strengths-based?

• Considering the current social and political climate and the effect this may have on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and the influence it may have on their participation or engagement – how might you or your organisation support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and show solidarity or allyship?

• Taking individual responsibility for cultural and historical education. Asking Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people to support your learning adds to the cultural loads that young people are already carrying.

• Self-care. There may be a level of discomfort that comes along with the process of unpacking important topics like colonisation and whiteness. While this work is vital to creating space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, workers and organisations should implement strategies and tools that support their wellbeing and learning journey.

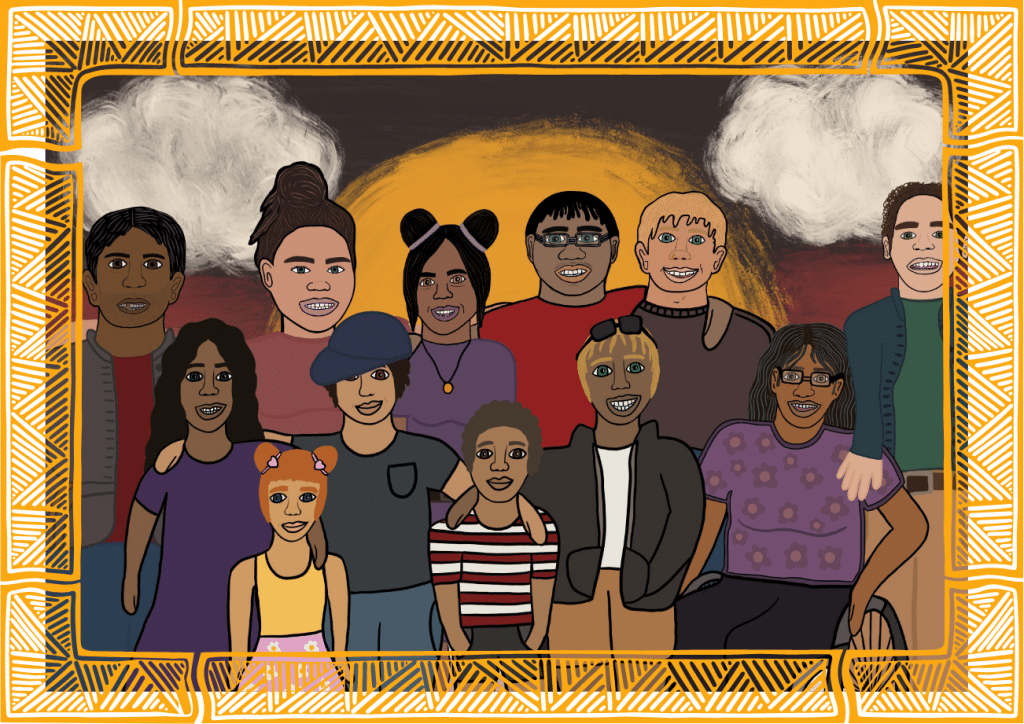

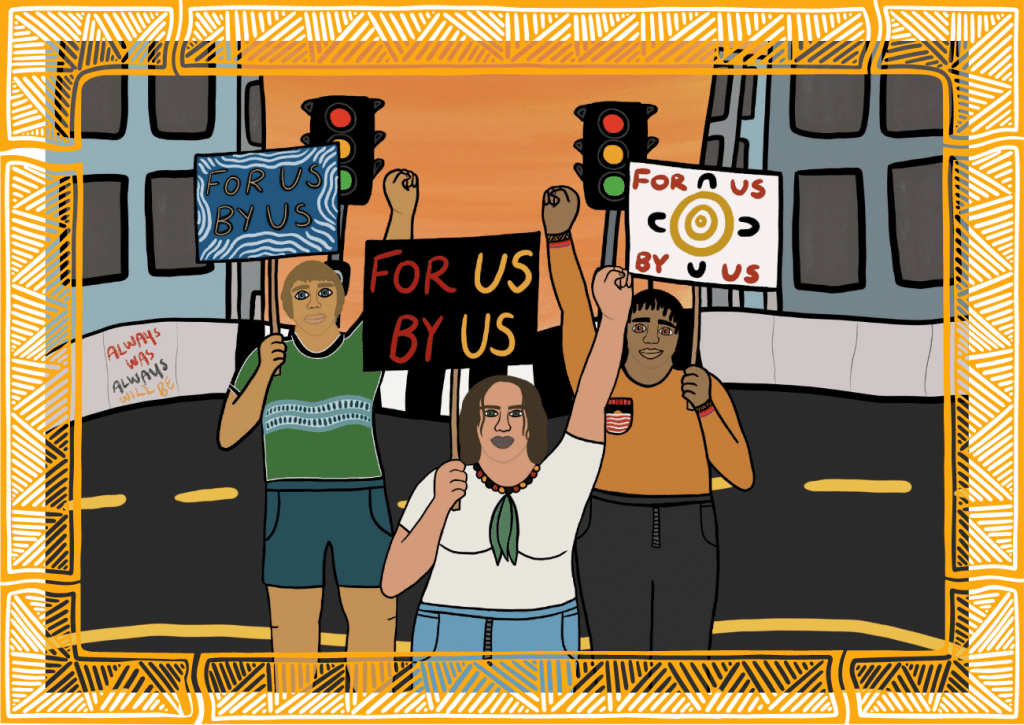

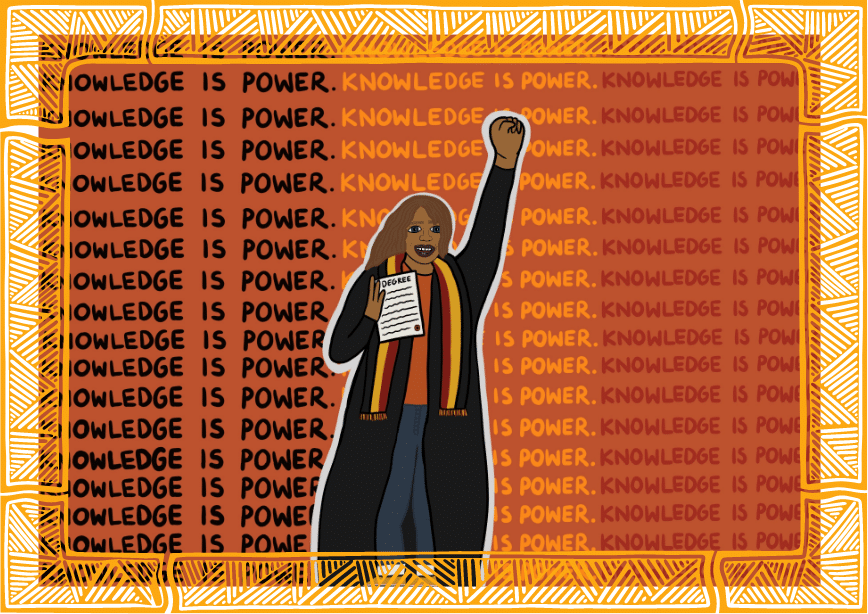

About the Wayipunga artist

Nakia Cadd is a proud Gunditjmara, Yorta Yorta, Dja Dja Wurrung and Bunitj young woman living on Wurundjeri country. Nakia’s art is inspired by her journey through motherhood, family and country. Nakia has been an Executive member of the Koorie Youth Council since 2014. The logo and all illustrations for the Wayipunga project are produced by Nakia.

Logo artwork story

The Wedge-tailed Eagle (Bunjil) is the creator spirit and totem of the Dja Dja Wurrung people. Bunjil guides our young people and protects them on each of their journeys, in the direction of the gathering circles. The land has different layers to it, representing the different nations, stories, languages and songlines. The footprints are there to acknowledge the past, present and future generations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

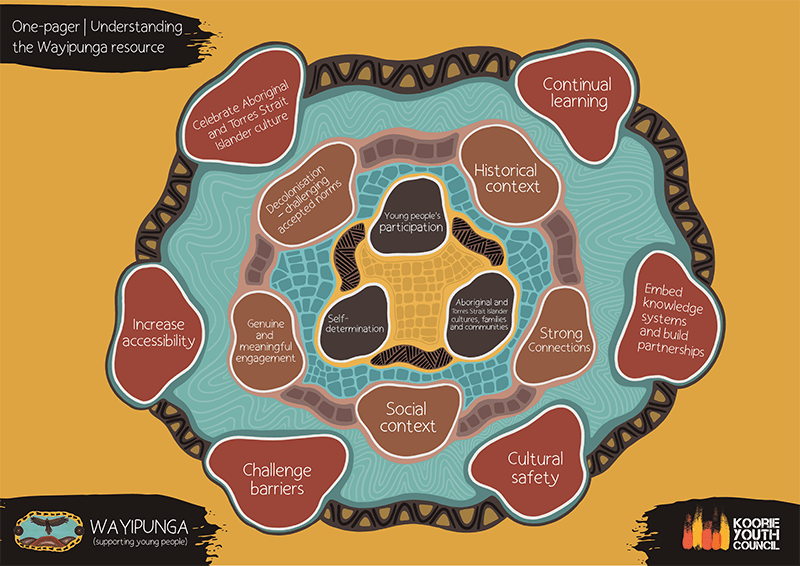

Understanding the Wayipunga resource

The mind map below is an overview of the Wayipunga resource. Starting with the values in the centre and rippling outward to the knowledge in the middle and actions on the outer circle, you can see how the sections of Wayipunga are interrelated and work to form an overarching framework for understanding youth participation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.

Thank you